This piece was co-written by Will Freeman.

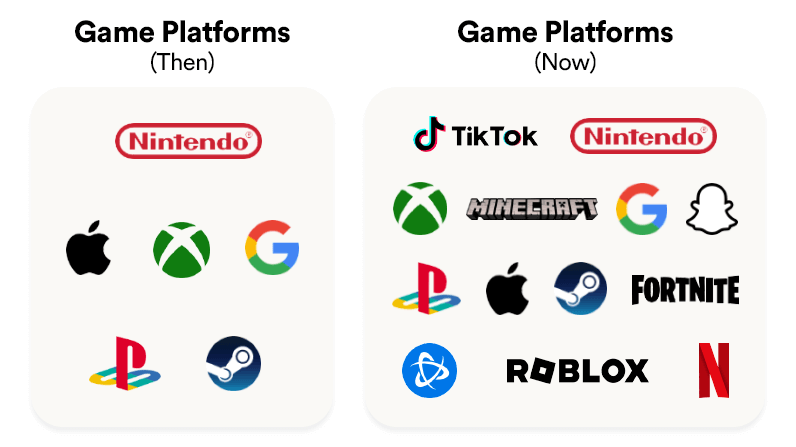

In the past, it was straightforward. Gaming platforms were hardware devices. We had consoles, PCs, and a scattering of handhelds. Developers made games for those devices, with the platforms (first-parties) and publishers holding the keys to success, exposure, and even release. Then came digital storefronts that served as platforms offering direct download, with Steam presenting the dominant model of blending point-of-sale and place to play. Mobile alternatives like the App Store and Google Play also threw their hats in the ring, as the console giants moved to digital with services like PlayStation Network and Xbox Live. What we didn’t realize at the time was that all of these platforms became – to a greater or lesser extent – walled gardens that place most of the power in the hands of those that host the platforms. A ‘walled garden’, in this case, refers to a closed platform, where the provider maintains restrictive control over what is hosted on the platform, and in many cases how that content is accessed, paid for, and even supported by different services and technologies. In many cases, walled gardens also lock players to the platform, blocking or limiting the likes of cross-play, cross-progression, and other cross-platform approaches.

Now we exist in the era of game streaming services, single-publisher subscriptions, battle passes, esports orgs, itch.io, and even individual game series such as Call of Duty booting up to what is effectively a platform. Netflix, TikTok, and Snap now host games, moving them somewhat into the territory of gaming platforms. And if a gig, branded experience, or community gathering can be held in Fortnite or Roblox, arguably individual titles are now presenting a new model for what ‘gaming platform’ can mean.

There are a lot of reasons that shift is underway. And a lot is underway.

Games, increasingly, are to be found everywhere, so what counts as a ‘platform’ continually expands. New technologies are allowing games to exist in more places, in many cases freed from physical disk or even digital download. The gaming audience hasn’t just grown in number significantly, but also in breadth. A wildly demographically diverse spread of audiences now long for all kinds of distinct gaming experiences, with different groups preferring different ways to access games. Live games have emerged as a dominant norm, meaning a shift in emphasis from release to ‘maintenance’, keeping developers more involved beyond launch, and more directly in-touch with their play. The likes of Twitch and Discord now let studios have a more immediate, direct relationship with the community, seizing a little power back from what was once the realm or the publisher. And in the era of the attention economy, where users are spoiled for choice in terms of access to content, platform loyalty is a fading phenomena. That alone may have a profound effect on how future platforms frame themselves.

That doesn’t mean the old platforms or models are going anywhere. Essentially, the platform landscape is getting busier, and even more complicated. And given the amount of money to be made by providing and holding a platform, the stakes are even higher now than seen in the last 30 years. Meta is spending tens of billions of dollars every year in the hopes it can secure platform control for the next generation of devices – namely VR, AR, and the wider XR spectrum.

So what does all that mean for the future? Is a new era approaching, where the walled gardens fall and more independent publishing platforms that promote the player-developer relationship flourish? It’s time to gaze at the potential and challenges ahead.

The Walls That Surround Us

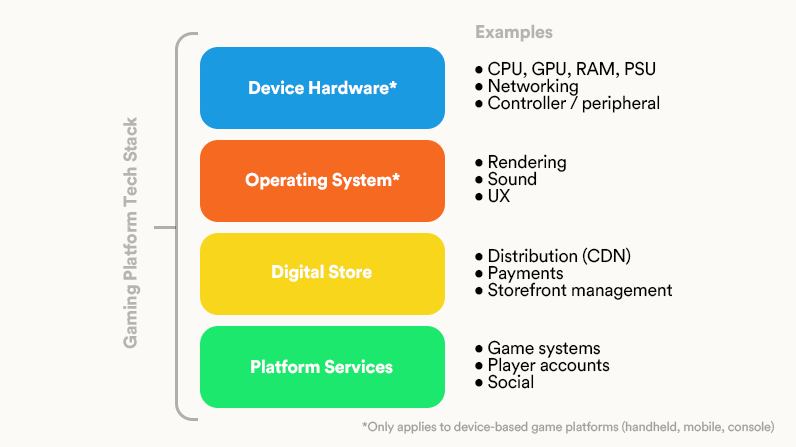

Before looking to the future, it’s worth framing what a ‘walled garden platform’ really is. To get a game on the likes of a first-party platform such as PlayStation 5 or Xbox X|S, you’ll need to meet a number of requirements. There’ll be performance and quality minimums to meet, and maybe even particular technologies or services you are required to use. You might have to sign some form of exclusivity deal, or accept limitations around cross-play, cross-platform and the like. You’ll need to go along with the platform holder’s wider systems, from achievement implementation though to publishing, marketing and community processes.

More than all of that, your game – including its design, fictional world, message and purpose, and more – will need to work for the platform holder. In other words, they get to decide if your game gets released. And you’ll need to agree with the platform’s typically rigid revenue share set-up.

In return for all of that, you get exposure, reach, and access to millions of players committed to the platform in question. Players will find and access your game in a trusted, familiar setting that speaks to quality and reliability, letting them organise and access their library in a single destination with a sole account. Meanwhile your game can make use of the platform holders’ online infrastructure – as long as you do it their way.

Bringing Down the Walls

It can be superb lounging in a walled garden, shielded from the rest of the world. The problem is, the walls. They can create a barrier that puts ownership of that precious player-developer relationship in the hands of the platform holder.

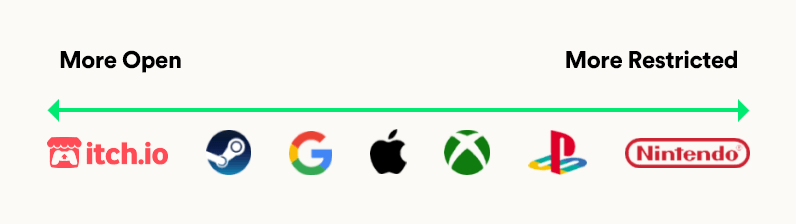

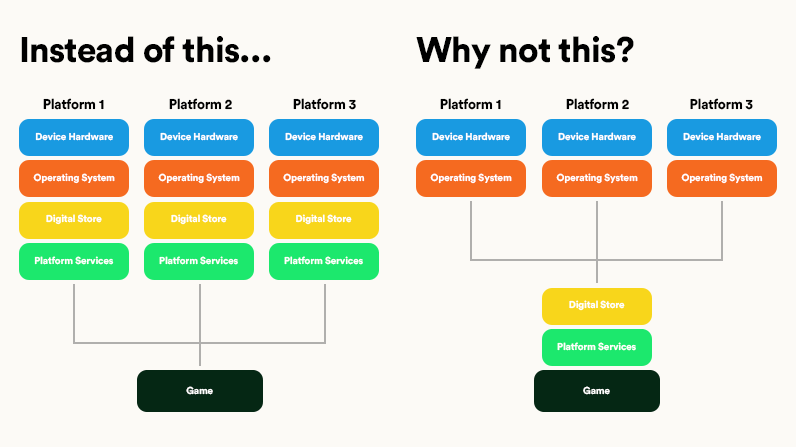

A better model? That would be one where a more open platform landscape becomes the norm; where developers have more creative and commercial freedom, getting to choose their own approach to making and maintaining games with their own blend of tools and services at the back end, their own approach to marketing, cross-play, monetisation, payments, distribution (while still protecting their business through the likes of DRM) and ultimately having a more direct relationship with their players. All while also enjoying the benefits of a trusted, robust platform that is seen by large audiences that can access everything via a minimal number of accounts. It’s a place we at LootLocker would love to see, because we believe developer freedom is better for the players, medium and business of games.

Something like that is emerging today. With Steam (and its rival Epic Games Store) we see an alternative presentation of the walled garden, where self-publishing is very much possible; albeit under the terms of a major player that owns and contains your audiences. The doorway is wide open to Steam’s walled garden – but the walls themselves hold the players within, maintaining that hold over the player relationship. Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store, meanwhile, offer a similar proposition. There’s considerable freedom, albeit under the terms of a strictly managed platform ecosystem.

More encouraging is the increasing prominence of Itch.io, which gives developers not just the ability to self-publish, but more freedom around testing early builds, technological and creative choices, backend and maintenance, and even revenue share. It remains a relative minnow 10 years since its launch, being dwarfed by Steam’s typical 120-million-plus monthly active users. And yet it continues to grow beyond its audience of core gamers, increasing presence and trust with the wider pool of consumers – even spawning phenomena like Among Us, and acclaimed hits such as Vampire Survivors. It doesn’t, however, offer the likes of DRM, or user accounts that can be taken into and across games. The backend is so basic, that while it offers freedom, it offers little punch. So Itch.io isn’t perfect, but may present a vision of where gaming platforms may go.

We’re also seeing a rise in laws that look to limit big tech’s power, and they’re having an impact here. In the US the Open App Markets Act is looking to address anti-competitive behaviour by prising open walled garden app stores – something Epic’s CEO Tim Sweeney is very keen to see. Over in Europe, the EU’s Digital Markets Act is proving to have a similar effect, having already been voted into law, and coming in 2024. Even just a few months ago Epic’s lawsuit with Apple forced Apple to allow games to link to alternative web stores, enabling game developers to circumvent platform fees and sell content outside of the platform ecosystem.

As such, it may just be that as player demand to access games in more places increases – in combination with walled gardens falling out of favour and devs increasingly wanting to build their own ecosystems while maintaining ownership of their relationship with players – that a new open era is ahead of us.

Of course, it may turn out that as new platforms grow, they too build new types of walls around their services or customers. We might continue to see new iterations of what a walled garden platform is, rather than a complete, absolute move to an open approach. It’s unlikely the existing walled garden platforms are going to open wide or disappear overnight. And yet, as games increase in reach and breadth, it seems that there will at least be considerable capacity for new, open platforms – including highly focused or developer-led ones. So let's consider that future, and what it might mean for your studio.

Platforming Potential

Considering we can now frame Fortnite or even Netflix as a platform, we should ponder what else might be possible. If (given the right tools) smaller developers collectively commit to ushering in a new open platform era, perhaps they could launch their own shared offering. Maybe even studios that work on the same or related genres or themes could build their own place for sharing, accessing and downloading games. Some established IPs might offer so much that they could establish a shared platform for every dev that has served it. Just like the proprietary engine, the ‘proprietary platform’ wouldn’t be easy, but it could bring many advantages (and is more achievable by far than building a game engine from scratch).

Perhaps we’ll see a rise in cause-based models like that seen with Humble Bundle increase in prominence. All those things are possible – and ripe with potential. Or maybe we’ll continue to see games increase their prominence on Netflix, Snap and TikTok, and blossom on many other ‘non-gaming’ platforms. With Epic now owning Bandcamp, for example, there’s new potential to shake up the relationship between musicians, game devs, and consumers. Maybe individual games will become platforms for music distribution.

Web3, blockchain gaming and ‘metaversian’ concepts are already with us, and don’t appear to be going anywhere. At LootLocker we’re watching that space keenly, and reserving judgement for now. So much of what the blockchain offers gaming is already possible with existing backend and publishing technology – but it's undeniable that notions like player ownership of interoperable game assets could theoretically shake up gaming to the point that the current system needs reinventing – establishing an opportunity to rebuild the platform landscape to be a more open, decentralised place (with or without the blockchain).

One thing is certain. A future where open platforms offer the dominant model for distributing, monetising, maintaining and sharing games will be a better place for games – unless, of course, you're majorly invested in a walled garden yourself. Player and developer needs are evolving – along with state legislation – to a point where platforms might simply have to open up. And a new generation of available, affordable technologies are giving devs more freedom to embrace and manage what was once the reserve of a handful of giants.

If it sounds unreasonable that developers might club together – or go it alone – to build their own platform, consider that a publishing platform could also be described as a ‘backend’. That’s certainly an oversimplification, but the platform isn’t the game. It’s what powers the game’s potential reach and legacy, connecting its players, payments, updates, events, performance and more. At LootLocker we’ve spoken many times about how a traditional backend is not too dissimilar to the tools that the publishing platforms provide – from matchmaking and leaderboards to player accounts and cloud saves. Many of these features are fundamental to what backends provide, as well as many publishing platforms. Publishing platforms do, however, connect the games that use them, in terms of the likes of player accounts and library access. A game that uses its own backend or a provided one, however, may not be able to ‘speak’ to other games in those ways. So does this all give us a hint as to where backends may be going?

A backend built more as a publishing platform could therefore be used as a vehicle to more easily launch across a range of platforms without losing the network effect by moving between walled gardens. Perhaps your upcoming PC wholesome rogue-like puzzler could do an effective soft launch on itch.io, before seizing an opportunity to leap onto TikTok, or those take early learnings and realise a strategic, informed move to Steam’s walled garden is best for your game. An independent publishing platform would allow you to do this while still maintaining a cohesive relationship with all of your players as they move from platform to platform.

Current first-party platforms in particular drive forward hardware development while providing a robust service for publishing games and a store marketplace or subscription service for discoverability. Yet they are far from perfect, particularly in how they ask developers to relinquish so many forms of power and leave the first-party platform as king-maker. Perhaps these platforms will see how audiences increasingly expect the likes of cross-platform as a standard expectation, inspiring some kind of opening up. Or perhaps they should focus their efforts on hardware and operating systems, and running their own content fortresses while leaving the publishing technology up to open third-parties. That would present an opportunity for new open and independent platforms, the innovation stirred up by competition from fresh challengers, and a chance for a new era of technology like LootLocker to step up and provide the same features as those walled gardens, but with increased flexibility, opportunity, and customisation for the ever changing landscape of gaming. And most importantly where the developers and publishers are in control of their data. ‘Publishing platform’ may soon describe a new, innovative blend of gaming technologies.

And as games are freed from these platform constraints – or the constraints of a few platforms – we may even see the medium evolve, with new genres or play experiences emerging. In combination with a new power balance between player, developer and publisher, that’s powerful – a future all devs should fight for.